MARCUS’ positions ON transportation and mobility in san francisco

Living Up to Our City’s Official “Transit-First” Policy

The San Francisco Transportation Context

San Francisco’s city charter, which functions as our “constitution”, specifies in Section 8A.115 that San Francisco’s official policy, as it regards to transportation, as being “transit-first”. With smog choking out American cities in the 1970s, San Francisco was no exception. City streets were clogged with private automobiles and the primary tunnel under Market Street for BART and Muni Metro were still under construction. Over 50 years ago, city leaders knew the menace that private automobile ownership, operation, and storage was on the limited streetspace available in the city and so in 1973 our charter was amended with language that prioritized transit use. Leaders in City Hall back then were cognizant enough to know the congestion, the environmental impact, and the inefficiency of allowing everyone in a city only seven miles by seven miles square was not a way to run a transportation network.

Nearly 50 years on, San Francisco has utterly failed to deliver on its own constitutional promises to voters. We don’t need to rewrite the rules on how our city streets and transportation network is to evolve in their uses, we just need to live up to the spirit and text of our city’s transit-first policy. Any and all changes to our streets, crosswalks, lights, buses, and trains must put the needs of the many over the desire of those privileged enough to own an automobile in the second-most densely-populated city in the United States to drive alone and park their cars for free on public streets. Marcus Ismael embraces not a radical, transformative approach to managing San Francisco’s transportation network, but an approach rooted in a nearly fifty-year old section of text in our city’s laws - one that puts the safe and free movement of people on buses and bikes, trains and taxis over single-drivers in space-wasting and polluting automobiles.

Pre-pandemic, the San Francisco Municipal Transit Authority, or “SFMTA”, ran 71 bus lines, 7 light rail lines which ran both above and underground (which is referred to as “Muni Metro”), 2 heritage streetcar lines along the Embarcadero and Market Street, and 4 cable car lines. Muni (for those out of town, this is pronounced “myoo-knee”) was the seventh-largest transit network in the country, carrying at least 700,000 riders daily with 55,000 of those riders on one line alone - the 38 Geary. When compared to any similarly-sized transit agency in the United States, Muni had more riders boarding per mile and more vehicles in operation at any given time. Yet it has always been one of the slowest with the average vehicle speed moving more than 8 miles per hour and, with a passenger per mile cost averaging $22 between its buses and trains, one of the most expensive to operate.

San Francisco’s transit system is a leading metropolitan public transport agency in the United States, but with one of the highest riderships - the aforementioned 38 Geary carrying the second most riders on any transit line west of the Mississippi - even greater than that of BART’s which transports only around 400,000 daily riders, pre-pandemic, Muni serves as the lifeline for those who want to or, in many cases, cannot get around without a car. Our system is one of the slowest, most expensive to run and riders are at a loss when the system doesn’t work. This plan is but a starting place to get San Francisco moving equitably and efficiently again.

the basics: buses that move, buses on time

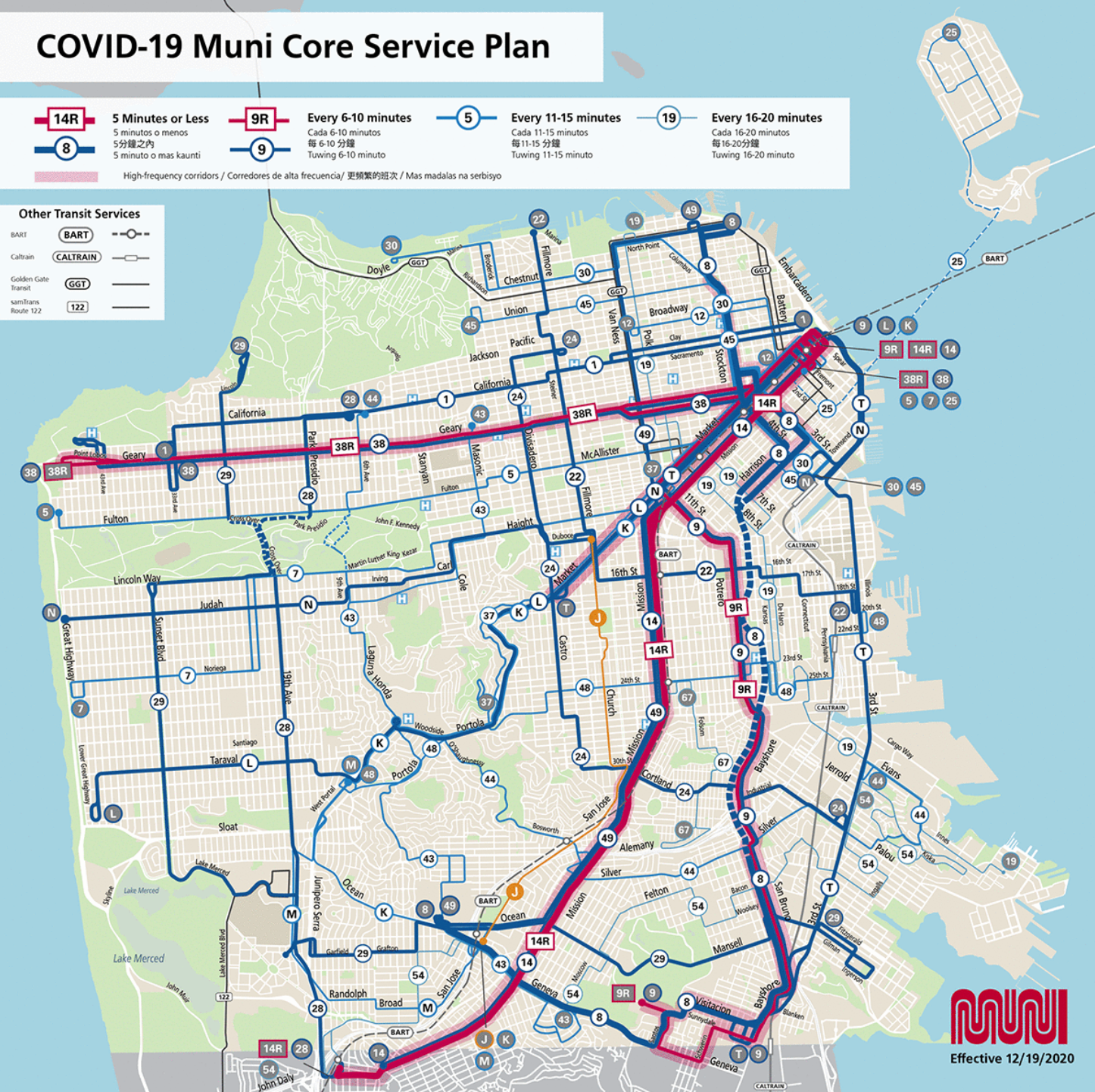

Before COVID-19, the most riders would have to worry about would be regular delays along their one commute line, or missing a transfer to BART or Caltrain, or the occasional system-wide shutdown which, when they happened, would leave riders stranded for hours underground or in line, above ground, waiting for bus replacements. The silver-lining of the pandemic as catastrophic as it has been for transit agencies across the entire nation, is that the core service plan implemented by Muni shows the 25 essential bus lines, of which three are rapid, and six core Muni Metro routes where even the smallest improvements to the rider experience can lead to the fastest turnaround for positive results.

Below is a map of the COVID-19 Core Service Plan highlighting the 31 routes that comprise the heart of the Muni system. As it stands, only the 14/14Rapid, 38/38Rapid, 8, 22, 30, 45, and 49, have regular, comprehensive red-paint transit-only lanes on the surface streets they operate. Several other lines with service frequencies every five to ten minutes could benefit from having red lanes on the long stretches of streets where there are multiple lanes of traffic. The 28 operates on 19th Avenue on the westside and while the primary reason why any city-sanctioned improvement doesn’t get off the ground is because the thoroughfare is a surface highway owned by CalTrans, the lack of political will means no projects to separate transit access from private vehicular movement exists. The 29 Sunset runs along Sunset Boulevard, a six lane arterial running north and south through the Sunset District and is the longest daytime running route in the entire Muni system, yet there is no red lane or intersection signal priority given to Muni buses. Moreover, an issue that plagues the 29 is endemic throughout the city: surface parking along curbs block passenger access to board buses at bus stops. If Muni took seriously making access along these core routes seriously, we’d see average speeds for Muni buses climb above the pitiful 8 mile per hour average and buses can hold to their scheduled frequencies.

25 bus lines and 6 light rail lines make up the core of the Muni system. If we fixed even just ten of these by configuring our streets and prioritizing the passenger experience, Muni would be a better system for everyone.

Muni’s Core Plan for service during the pandemic preserves 25 bus lines and keeps 6 light rail lines operating at surface level. These essential routes mark the biggest opportunities for improvement in the immediate term.

SAFER STREETS FOR ALL USERS

San Francisco’s streets are a mess. The curbs are almost exclusively set aside for free storage of private automobiles on public property; the sidewalks, if not covered in debris, human waste, or tents, are woefully inadequate to providing the ease of access one would expect in a major city; and the infrastructure designed to move people who get around through modes other than driving is what often leads to untimely, unnecessary, tragic deaths. Take for instance San Francisco’s idea of a bus stop: nothing more than a stripe of yellow painted on the nearest utility pole in much of the city. The adjacent curb space is often packed with parked cars forcing pedestrians to weave tightly in between them or step out into oncoming traffic to be seen by a bus driver. This isn’t just accessible to able-bodied individuals, it impedes the access of persons with mobility considerations like wheelchairs, walkers, or infant strollers. San Francisco’s crosswalks are a mess of unmaintained stripped paint at worst and inconsistent paint jobs and crash cones at best. The poor design of our streets to accommodate those who move through the city in ways other than in a car is as discompassionate as it is deadly.

We must take a firm priority in making our sidewalks, crosswalks, and streets safer for pedestrians, the elderly, the disabled, families with children, and bicyclists. More transit lanes; barrier-separated bicycle lanes in a cohesive, city-wide network; wider crosswalks in narrowed intersections; wider sidewalks and enforcement of blockages caused by parked cars or construction; and proactive enforcement by SFMTA officers at critical intersections throughout the city.

SEAMLESS, timed TRANSFERS and unified fares

San Francisco is at the heart of an urban core that crosses the Bay over to Oakland and continues on 40 miles south to San Jose. Movement between the three cities is one of the keys to why the Bay Area became and remains one of the most culturally and economically vibrant areas in the United States, yet the movement itself has never been easy. A resident in the Richmond District of San Francisco would have to pay $2.50 to ride Muni to downtown San Francisco then tack on an additional $5 to ride BART over to Oakland or $10 to ride Caltrain down to San Jose. The transfers between transit agencies, from bus to train, are not timed nor is there a fare discount for taking transit all the way. The amount of time spent traversing San Francisco itself would take no less than 50 minutes which amounts to four trips back and forth between Oakland and San Francisco’s downtowns and past Redwood City from San Francisco. Yet this grueling, hours-long journey isn’t just time-consuming, it’s expensive and it’s not the only one.

As the cost of housing goes up in the urban core, those that can afford to move but remain in the Bay Area most add additional legs to their journeys - some take ferries from Marin, Sonoma, and Solano Counties, others take Amtrak from as far as Sacramento, others still take ACE from Stockton to reach Silicon Valley - and this is on top of needing to connect to yet another, localized transit agency. In total, the Bay Area has 27 different transit agencies spread across trains, buses, and ferries and yet none of them connect in a meaningful way that would make commutes easier or more affordable.

Enter the plan proposed by Seamless Bay Area that establishes a zone-based fare structure irrespective of mode of transit that grants riders faster service and unlimited transfers while paying their local fare. According to Seamless Bay Area, most trips taken on transit today are short trips under 6 miles. Low income riders are more likely to take short trips than long trips, pay using cash, transfer between agencies, and pay single fares instead of purchasing passes. Such a plan would not only encourage the use of transit for short-distance trips, but allow for affordable commutes and establish a daily, weekly, and monthly fare caps to ensure lower-income transit riders are not hurt by high upfront costs for choosing the sustainable, better mode of getting around: public transportation.

The next steps to lead the Bay Area into a unified transit future are two critical things: coordinated schedules to allow seamless transfers from local bus and light rail routes to the trunk of the Bay Area’s metro system BART and a singular, unified governing authority to establish fares and revenue sharing. Read more about Seamless Bay Area’s plans for greater reform here.

FULLY ACCESSIBLE TO RIDERS OF ALL ABILITIES

As mentioned above, San Francisco’s transit stops outside of the busiest corridors are woefully inadequate in ensuring ease of access for riders of varying mobility considerations. Forcing Muni riders to squeeze between parked cars on the curb to reach the bus on the street, lift up their grocery carts or baby strollers from high curbs, or be at the mercy of the availability of boarding ramps or elevator maintenance is no way to run a transit system on which hundreds of thousands of riders depend annually. From boarding ramps on Ocean Avenue, Church Street, Taraval Street, and Judah Street that do not stretch out to fully allow riders in the second set of train cars on Muni Metro’s light rail vehicles to board and disembark to boarding islands on those same streets situated in a way that forces riders to cross one lane of moving, oncoming traffic to reach them, San Francisco’s accessibility on what are meant to be its most accessible vehicles is a joke.

Street parking in loading zones for buses is another egregious example of how little regard the SFMTA shows for its customers and parking along the curbs of some its tightest streets impedes the free and safe movement of its buses. The long headways in between buses keeps passengers at the mercy of the weather - often the cold and fog. Constant breakdown of elevators and escalators in the Market Street subway plague the ease of movement for elderly and disabled passengers. The lack of weatherized shelters above most bus stops and the lack of seating subject even the average user to miserable conditions.

All of these are easy, straightforward fixes that require two things: money and political will. Ultimately, the will to make changes that will directly benefit the lives of working San Franciscans can only be found in those empathetic enough to prioritize making these immediate changes.

TOPLINES

Faster, frequent bus service.

Fully-accessible transit access.

Protect pedestrians, families, and bicyclists.

Timed transfers to other transit services.

Integrate fares across all Bay Area transit providers.

Move toward free transit.